The Great Meme Recession

Have you ever seen a meme from 2011 and wondered why they’re so different from the memes we see today? Memes in the past seem to hold more weight to them, more of a period uniqueness to them that lets us fully understand what the most important political, social and leisure content of the time was. I believe memes speak a lot about society – in fact, they are driving forces in our society that depict what topics are of great importance and what is less memorable. However, with the growth of consumerism and what I will later define as ‘skimming culture’, we have entered a pattern where it seems no new memes settle down into the ethernet, and any that do pass just as quickly as they came on. If we define the 2009-2015 Internet meme culture as the Great Meme Renaissance, and 2016-2019 as the Golden Age, where we sit now is the epoch of the Great Meme Recession. In order to understand the Great Meme Recession, let’s take a look at what a meme is and a brief history of the meme.

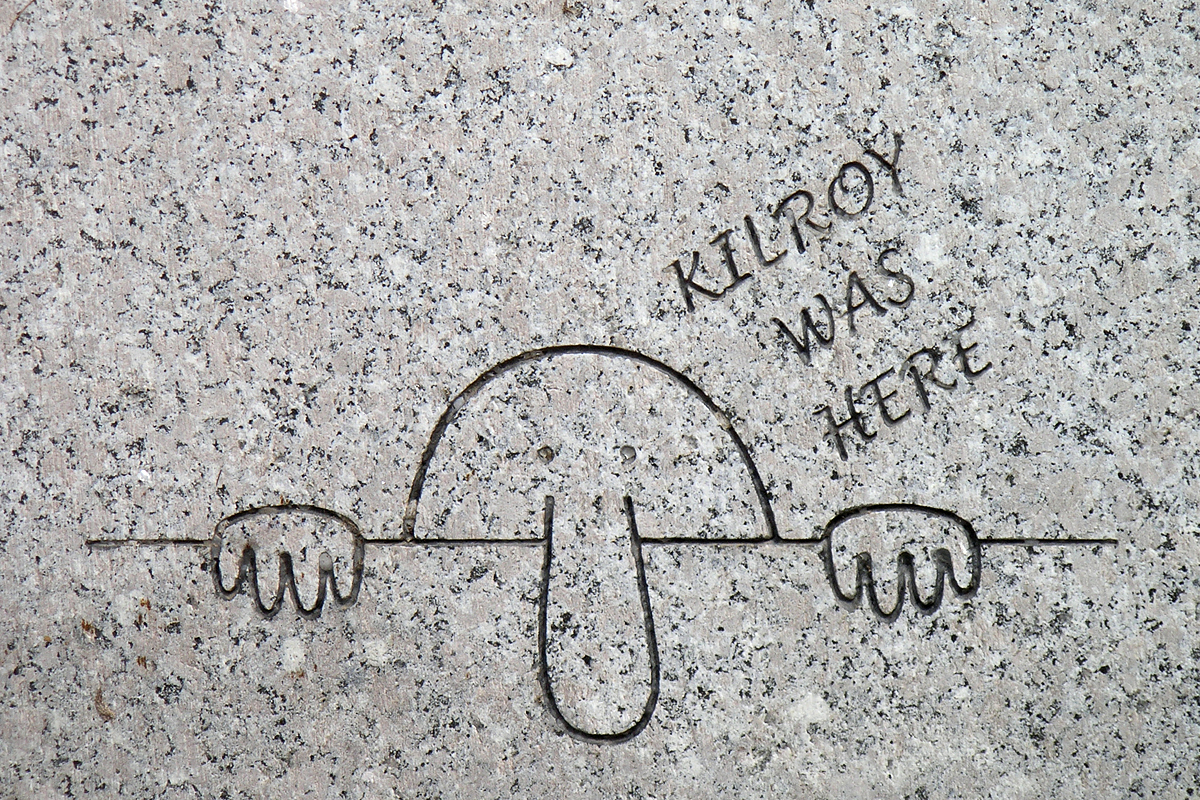

Memes are a comedic cultural tool in which the same template is relayed and imitated to address different concepts, resulting generally in the same image or wall of text following the same template, with slight variations. However, today you can generalise any satirical digital image as a ‘meme’, which alludes to the later presented idea of skimming culture. Memes are tool of social unification, transmitting ideas across culture in easily digestible formats. Memes influence our physical culture and always have, and the introduction of digital culture has accelerated this process. The term meme was coined by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, defined as “cultural units of information.” He argues that unlike biology, memes are cultural genes that are socially controlled but aid the evolution of our cultures through the way they replicate and develop ideas, ideals, cultures and customs. Long before planking, parkour and the Harlem shake existed, we can see the 1950s pop culture challenge of ‘phone booth stuffing’, the 1930s ‘dance marathons’ (which still exist in some societies such as the Netherlands – ‘De Dansmarathon’ 2021 was a live-tweeted event where couples competed for a 100.000 € prize). Most notably, ‘Kilroy was here’ a WWII meme dedicated to graffitiing buildings and landmarks with the picture of a cartoon man called Kilroy. Probably the world’s longest standing meme is phallic symbols – or the beloved dick joke.

So what is the driving force behind the death of the culturally essential meme? My belief is that the fall of meme culture lies with the burden of the falling attention span of the internet, owing to short and snappy TikToks (and formerly, 6 second Vines), Instagram political activism in the form of infographics and a tailored Explore page that seeks to grab your attention – making it impossibly difficult to fixate on one or two great memes of the month as we are always looking for the next novel ‘fix’ and the newest thing. While we do still commemorate older memes (I’ve lost The Game several times this year already… sorry!), they now belong to the internet subculture of “2011-2015 memers” which is a dying population as Generation Z enters the Internet met with Instagram and TikTok, mobile-interfaced social media as opposed to the previous culture of what I would call “dedicated computer time”. We can now engage with memes during a boring moment of conversation, swipe through some TikToks on our 30-minute lunch break and read some infographics as we wait for the shower to get hot. This contrasts previous experiences of the Internet where you would sit down and put aside your evening to spend time roaming the Internet – something to look forward to and engage with to the fullest.

Now, we are living in autopilot and on an as-and-when Internet basis, and we live in a skimming culture. I would define skimming culture as the speed in which mobile-phone media consumption has encouraged us to take in media, not by reading or assessing it fully but by taking in bursts of information as quick as possible to evaluate whether it is of interest to us. How many of us will see a chunk of text and decide to read the whole thing? We read the opening, or skim a few lines to determine whether it is of interest to us, and we apply the same logic to videos, images, comments sections, WikiHow articles and so on. As mentioned earlier, the definition of a meme has expanded to include any image found on the internet with a comical undertone or overtone – which suggests that there is no cultural collective to these images, just images or text you either have seen or have not seen and no need for continuity like our previously defined meme. There is no need for a fixation on these images if they do not grab our attention for long enough, because we can just move onto the next best thing – or skim to the next page. Skimming culture is not a unique internet phenomenon - in fact it has translated through to the attentions spans of day-to-day life outside of social media. It’s much more difficult to sit down and read Anna Karenina, or to watch a 30 minute lecture on a boring topic. Today’s patterns of consumerism and political discourse reflect skimming culture, with us taking in the most attractive and novel headlines about our prime minister having sex with a pig, or believing that North Korea banned certain haircuts without wanting to dig further to verify its truth. Truly, we want the interesting to be handed to us on a silver platter, and with websites like Shein and Aliexpress presenting us thousands of cheap and easily accessible options we can skim through, we no longer have to settle on saving up for that nice jacket when we can buy a lookalike for cheaper AND a second jacket, and an in-fashion hat too. We won't sit and listen through a playlist someone made for us to listen to, and some clubs have placed a mobile-phone ban on the dancefloor since it kills the aspect of 'living in the moment', because when things get too dull we need that quick dopamine fix.

Memes have become so niche, paralleling the sharp increase in consumerism of niche and individualistic commodities. The personalisation trend in consumerism has extended to our meme culture, where instead of everyone owning the same item or taking in the same media, you are expected to own/engage with as many consumer goods as possible, and to an extent our identities now belong to our consumerism and our patterns of engaging with commodities. In the past you could use a meme template to apply it to any general concept to create a relatable meme, such as a rage comic. Now, our new norm is the following: the more far-fetched and obscure a meme is, the more successful it is for it’s 15 minutes of fame, or more aptly, 15 seconds of fame. The more unique your meme is, the more absurdist it is, the more it is celebrated as a beacon of individualism, rather than the previous collectivist culture of relatability to every-day phenomena. One meme template would previously satisfy one general niche – such as Bipolar Owl or Socially Awkward Penguin. But now, the TikTok FYP is far too customizable to mean anything or unite anyone under an umbrella of the comical human experience. Individualism has brought skimming culture to its peak - see fast-fashion, with Youtubers creating videos of their $1000 Shein haul, and new eccentric AliExpress clothing popping up every other second that appeals through the sheer idea that no one else has it yet.

There is no longer a target audience like there was back in the day, at the risk of sounding geriatric. If you’re not in on it, it’s difficult to get in on it because meme waves pass so fast. You have to be there for the initiation of a meme or be introduced by someone who was, because as testified by my friend Isis Wong, "they either die too quickly or get too annoying." In 2011 if you were an avid internet user you would’ve been exposed to certain content we collectively know as internet culture – but what is internet culture now? There is no LOLcat, no weight to being Rick Rolled, no more Don't Hug Me I'm Scared, no fantastic references to classic Spongebob quotes. It's hard to define internet culture as anything more meaningful than simple consumerism. There is a social expectation and perhaps pressure of consuming as many forms of media (social, political and entertainment) as possible, take in as much content as possible to stay ‘in on it’ – consequently, there is no unified meme culture. You will belong to not just one but several niche meme subcultures such as on_a_downward_spiral or thearchbishopofbanterbury or turnleftist1917 which are absurdist memes, satirical representations of UK culture, and memes for the political left respectively. We instead build our own individual meme cultures which is a great way to develop your interests and sense of humour, but doesn't hold the same weight as being part of a true community of like-minded memers.

The death of Flash is likely a contributing factor, owing to the sudden destruction of flash-based games such as dressupgames.com, witty flash animations (rip Newgrounds.com), classic memes such as the badger video, the death of hentai games (this is an important subculture okay). The death of flash is likely linked to mobile phone culture, which disabled flash-based animation. Even the death of cultural hubs and personality-shaping websites and communities such as Neopets and Habbo Hotel, which are now essentially deceased. The internet’s present-moment oriented nature, where nothing lasts forever despite being fed that your images will stay online forever, has led to the death of social media platforms such as Vine and MySpace, destroying communities and their associated cultures. Wizard101, Chicken Smoothie, Scratch.mit.edu and Webkinz are no longer even a fraction of their former popularity – the majority don’t even know what these are anymore. Fantage is dead, Build-a-bearville gone. It is through moving past these communities that the internet lacks any tangible sense of unity anymore, which creates for lacklustre memes as we no longer have anything in common with each other.

Another aspect is the ostracization of the Internet from the real world; I would argue that the Internet has become its own digital society separate from the physical worlds and cities each member belongs to. Just like in any society, there’s new niches and subcultures which we belong to meaning the Internet as a whole is no longer its own subculture, just the norm. It has become so global and expansive that there is no longer any universality to being an Internet user versus not. We no longer have anything in common with a fellow Internet-user because their experience is distinctive to your experience to my experience; we create our own culture of what internet memes are and what music is big and what fashion and political ideology is relevant. Because of this, we lack the concrete sense of ‘real’ celebrities, as we engage with entertainment from behind a screen, and comment on it to others behind a screen that happened upon the mutual interest of our distinctive subcultures. Doja Cat, for example, is a major Internet celebrity, but if you mentioned her to an Internetless generation, they would respond with “Who’s that?”. There are thousands of niche Internet micro-celebrities, and our prejudices contribute to the fame of certain people. The TikTok algorithm is infamous for favouring Eurocentric white features, and measuring ‘objective’ beauty (or the beauty standards that are imposed on us today) to boost certain TikTok creators. It always tends to be a slightly above-average white guy who ‘gets it’ (Bo Burnham, for example) or a woman who meets conventional beauty standards. They don’t need to contribute anything of real value; the token white man can just say something ‘based’ from time to time. Therefore, I argue nothing and nobody is a major cultural icon anymore. Nothing holds the same weight as The Spice Girls, Nirvana, Metallica, Red Hot Chilli Peppers. The music that comes on the radio is either the same recycled pop/house beat or a trending TikTok song. And yet we subscribe to the idea that anyone can make it if they try hard enough – the myth of meritocracy all over again that is proven so by social media algorithms.

The way the ‘net operates now is so distinguished from the aforementioned 2004– 2014 (approx.) universality of either being an avid internet user or not. Tight-knit yet culturally dominating communities such as the My Little Pony, Touhou or Warrior Cats all experienced the same memes at the same time at the very moment they unfolded, or if you were a new-comer you would be mentored and therefore accustomed to the memes of the community as you assimilated into the culture you were joining. Now, these communities are just another common interest. There’s no devotion to the forums, no more ask-blogs or universally reblogged memes in the Tumblr community tag. In fact, even just on Tumblr memes would spring up and dominate the website regardless of your intention on Tumblr. As a Tumblr user, you would know about Dashcon, the Homestuck cop, none pizza with left beef to name a few. But now, culturally iconic memes or ideas are scarce. Community is increasingly niche and gatekept as media becomes repetitive, diluted and unoriginal. And even great media in its rare form, such as Squid Game, does not develop a community but dominates every social media for a couple of months as the masses are pressured to consume it, before dying as quickly as it sprung up.It appears that no meme that has arisen in recent years has aged well, unlike our constant nostalgic references to past memes that have stuck, through the recent rise of Wojak faces and making fun of old clearly fake Tumblr text posts (again, see Homestuck cop). Even fashion today is cycling through referencing previous decades of fashion and culture. Y2K is perhaps the biggest influence on present-moment fashion – with it we try to mimic relics of Y2K culture such as Paris Hilton and Britney Spears, and perhaps most distastefully we are imitating the culture of misogynistic beauty standards and toxic hetero-attraction (such as half-joking about marrying predatory rich old men to kill them off). It feels as though we have reached a dead-end in creating cultural richness, to the extent we are dependent on the past to fuel the future of memes and subcultures. To summarise, memes are a dying artefact as the internet becomes increasingly globalised and separate; there is a lack of tangible community in the same sense it was tangible in the past. Meme culture has become diluted, accelerated in nature and individualistic, effectively destroying the collectivism and community that made memes so great in the past. In addition, it seems we have run out of new ideas and massive icons that brought our society together in the past; everything seems to be recycled, and anything new and innovative becomes over-consumed and dominates for maybe one month or two, before all but disappearing from the Internet altogether. We have come to an era where we are over-reliant on icons from the past to develop icons of the present. We are desperate for something to cling to as we all come to the slow realisation the Internet is not what it used to be. R.I.P meme culture.

Comments

Post a Comment